WHY YOU SHOULD KEEP A JOURNAL丨为什么你要写日记

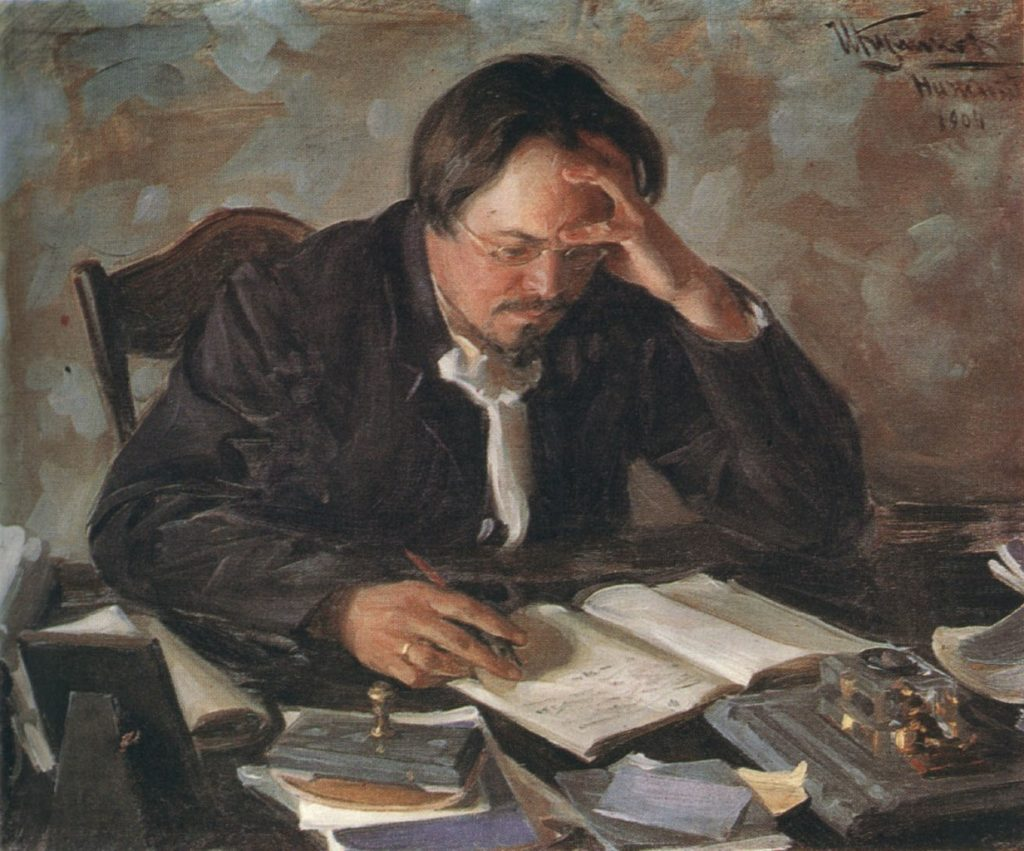

What should in an ideal world define someone as a writer isn’t that they publish books, or give talks at literary festivals or wear black; it’s that they belong to a distinct group of people who — whenever they are confused or in distress — gain the greatest possible relief from jotting things down. ‘Writers’ in the true sense are those who scribble — as opposed to drink, exercise or chat — their way out of pain.

在一个理想的世界里,把一个人定义为作家,并不是因为他们出版书籍,或者在文学节上发表演讲,或者穿着黑色衣服; 而是因为他们属于一个独特的群体,无论何时他们感到困惑或者痛苦,他们都可以通过草草记下事情来获得最大程度的解脱。真正意义上的“作家”是那些涂鸦的人ーー而不是喝酒、锻炼或聊天ーー他们摆脱痛苦的方式。

The act of writing, especially in a journal or diary, is filled with therapeutic benefits. So deeply do certain ideas threaten the status quo, even if they ultimately offer us benefits, the mind will ruthlessly ‘forget’ them in the name of a quiet life. But our diaries are a forum in which we can raise and then galvanise ourselves into answering the large questions which lie behind the stewardship of our lives: What do I really want? Should I leave? What do I feel for them?

写作的行为,尤其是在日记或日记中,充满了治疗的好处。某些想法对现状的威胁是如此之大,即使它们最终能给我们带来好处,大脑也会以安静生活的名义无情地“忘记”它们。但是我们的日记是一个论坛,在这里我们可以提出并激励自己回答隐藏在我们生活管理背后的大问题: 我真正想要的是什么?我该离开吗?我对他们有什么感觉?

We may not quite know what we want to say until we’ve started to write; writing begets more writing. The first sentence makes the second one clearer. After a short paragraph that was summoned from apparent air, we start know where this might be going. We learn what we think in the process of being forced to utter ideas outside of our swampy minds. The page becomes a guardian of our authentic elusive self.

在我们开始写作之前,我们可能不太清楚我们想说什么; 写作催生更多的写作。第一句使第二句更清楚。在短短的一段话之后,我们开始知道这可能会发展成什么样子。我们在被迫说出我们思想之外的想法的过程中学习我们的想法。这一页变成了我们真实而难以捉摸的自我的守护者。

Here we can make vows and attempt to stick to them: No more humiliation! The end of masochism! Ordinary life can seem to have no place for stock-taking and moments of grand enquiry. But the page demands and rewards them: What am I trying to do? Who am I? What is meaningful for me? We’d never get away with such things at the dinner table, even among people who claim to love us — but here they make sense.

在这里,我们可以发誓,并试图坚持下去: 没有更多的耻辱!受虐狂的终结!平凡的生活似乎没有盘点的余地,也没有宏大的调查时刻。但是页面要求并奖励他们: 我试图做什么?我是谁?什么对我有意义?在餐桌上,我们永远不会做出这样的事情,即使是在那些声称爱我们的人中间ーー但在这里,这些事情是有道理的。

We can look back at what we’ve written and understand. The page is a supreme arena for processing. We can drain pain of its rawness. We can get used to disasters and stabilise joys. We can turn panic into lists. Five ways to survive this. Six things I am going to tell them. Four reasons not to despair. We won’t need to be so jittery in the world outside after we have told the notebook all this.

我们可以回顾我们所写的,并且理解。页面是处理的最高舞台。我们可以吸干它的痛苦。我们可以习惯灾难,稳定快乐。我们可以把恐慌变成清单。五种生存之道。我要告诉他们六件事。不要绝望的四个理由。在我们把这些都告诉笔记本之后,我们就不必在外面的世界里如此紧张了。

The page becomes a laboratory in which to try out what might shock and surprise. We don’t need to honour everything we say. We’re giving it a go and seeing how we feel. It’s the first draft of a letter to ourselves.

这一页变成了一个实验室,试验什么可能会令人震惊和惊讶。我们不需要尊重我们所说的一切。我们要试一试,看看感觉如何。这是写给我们的信的初稿。

Looking back at what we have written should be embarrassing, if what we mean by that is hyperbolic, disjointed, uncertain and wild. If we aren’t appalled by much of what we have said to ourselves, we aren’t beginning to be truthful — and therefore won’t learn.

如果我们所指的是夸张、脱节、不确定和狂野,那么回顾我们所写的东西应该是令人尴尬的。如果我们对自己说过的话不感到震惊,我们就不会开始诚实ーー因此不会学习。

If in ordinary life we make a little more sense than we might, if we are a bit calmer than we were, it’s perhaps because — somewhere in a drawer — there are pages of tightly compressed handwriting that have helped us to understand our pain, safely explore our fantasies and guide us to a more bearable future.

在日常生活中,如果我们比以前更有意义,如果我们比以前更冷静,也许是因为在抽屉的某个地方,有几页紧紧压缩的笔迹帮助我们理解我们的痛苦,安全地探索我们的幻想,并指引我们走向一个更可以忍受的未来。

评论区